A panda walks into a bar and eats shoots and leaves. Lynne Truss’ book with that title showed how punctuation matters in a sentence. In both instances, the panda had a meal. What isn’t clear is whether the meal was plant based or whether a firearm was involved.

Punctuation matters. Words do, too. They matter greatly in science, where miscommunications occur with the public with common words. The word “theory” in general usage means a guess. In science, a theory is a statement of what one believes based on a compilation of facts. Gravity is a theory. So is relativity. So is evolution. Our understanding may be incomplete, but we are hardly guessing at what is occurring, and a great deal of our daily lives are made easier because of theories. Newtonian mechanics got us to the Moon, but we need Einstein’s relativity to calculate Mercury’s orbit accurately.

Two or more sides to a story don’t mean all sides have equal weight. They do on a die, but not the sum on a pair of dice. The numbers 1-6 come up with equal probability for a die. There are 11 possibilities with the sum of two dice, but the probabilities are very different for each, from 1/36 for 2 (or 12) to 1/6 for 7.

There is uncertainty in scientific results. Unfortunately, the lay public views “uncertainty” differently. In general usage means one isn’t sure and in fact may be guessing. Malpractice lawyers love to misuse these words, “Were you uncertain?” If one answers “A little,” then the next comment may be, “So, you really didn’t know what was going on, did you?” putting words in one’s mouth and treating the uncertainty of a diagnosis as a character flaw and a substandard physician. I’ve been there. When I practiced neurology, I had many instances where I was uncertain of the diagnosis, and frequently the patients, through having been told by someone else or not listening to me, felt that I had no idea what was going on. Neurology is one of the most difficult specialties in all of medicine, but I was usually considering several diagnoses. Also, the fact that I could not cure a person with a severe brain injury didn’t mean I was uncertain of what was going on.

We demand temperature predictions to the nearest degree and rainfall’s beginning to the nearest minute despite inability to correctly predict these regularly. A temperature range would be a far better forecast.

Uncertainty in science is vastly different from how the public perceives it, and it is one reason many phenomena with a high degree of confidence (another important word) are not believed, because of such uncertainty: “they really don’t know for sure.” The difference is that uncertainty is usually quantified in science. If we say we are 95% confident of a result, that means if we ran one hundred simulations or saw this particular phenomena one hundred times, 95 of them would contain the value we were measuring. We wouldn’t know which 95, but it is far from the “anything can happen,” approach, and it doesn’t mean that 5% of the time we don’t have a clue. Consider “95% certain there is a fracture in your hand,” a probability, which when studied was far less. It doesn’t mean that there is a 95% probability the interval is right; it either is or it isn’t, and that makes no probabilistic sence.

If one tosses a fair coin four times, one would expect it to come up heads twice. This is the expected value, 50% probability of heads each time*4=2. But a priori, we are uncertain. It may come up heads all four times with probability 6.25%, one-half multiplied by itself four times. Or, it may come up three heads 1/4 of the time, two heads 3/8 of the time, one head 1/4 of the time, and no heads 1/16 of the time.

If somebody told me I would have to pay them a dollar for every time exactly two heads occurred, because that is the expected value, and I would have to pay them a dollar every time it came up some other number, I would take that bet in a heartbeat. Am I certain of winning? No, but the probability—future oriented—of my winning is 62.5%, and that is solid. I am uncertain what will exactly happen, but I am highly certain what the probabilities are and my expected gain. Casinos don’t take money from everybody; they occasionally lose big, but over time, they win, and furthermore, they have a very good idea of the range of their winnings.

With 10 coin tosses, there is a 1.1% probability that there will be 9 or 10 heads. The expected number, 5, has slightly less than a quarter probability of occurring, no longer 3/8. Notice that extreme events still occur but with much lower probability with a few more attempts.

Toss a coin 20 times and the likelihood of 90% heads or more is on the order of 1 in 5000, not 4.5%, and the probability of 50%, or 10 heads, is less, about 1 in 6. The likelihood of exactly half, the expected value, diminishes, but the variability decreases much faster, and more and more of the outcomes cluster closely around 50%, even if they are not 50% exactly.

It’s like weather and climate. There are many who say if we can’t predict the weather accurately, how can we possibly predict climate? It’s because climate is made up of many weather events over a long period of time, where exact averages are not likely to occur very often, but the variability around those averages is much less. Indeed, extreme values will be far less likely unless the system itself changes. The issue for science is to try to predict as accurately as possible, but science recognizes that there is always a certain degree of uncertainty—not that we have no idea what is going on, but exact predictions of many phenomena may be impossible. Instead, there is an interval, the “plus or minus,” stating the range where the true value of the parameter of concern is believed to lie. We will never know that true, exact value, but we are very confident in its interval.

Uncertainty doesn’t mean “it can be anything.” No, 100 consecutive heads cannot occur with any sensible probability. Indeed, even 75 or more heads has probability 0.0000002, the likelihood of guessing a second chosen at random in the past two months. It’s only about a 1 in 6 chance there will be 55 or more heads.

I have long argued in climate scenarios that those who believe there is no significant global warming occurring must offer a confidence interval of what they think the temperature will be in 10, 50, or 100 years. The interval would be expected to contain zero, no change. It is not enough to say the current data are wrong. What is the margin of error? What is the confidence? It can’t be 100%, for that would be saying one could look at thousands of variables and know exactly how they would behave.

Uncertainty is reality. We embrace it in science, do not consider it a sign of weakness but a strong statement of “we could be wrong, but this is how wrong we can reasonably expect to be.”

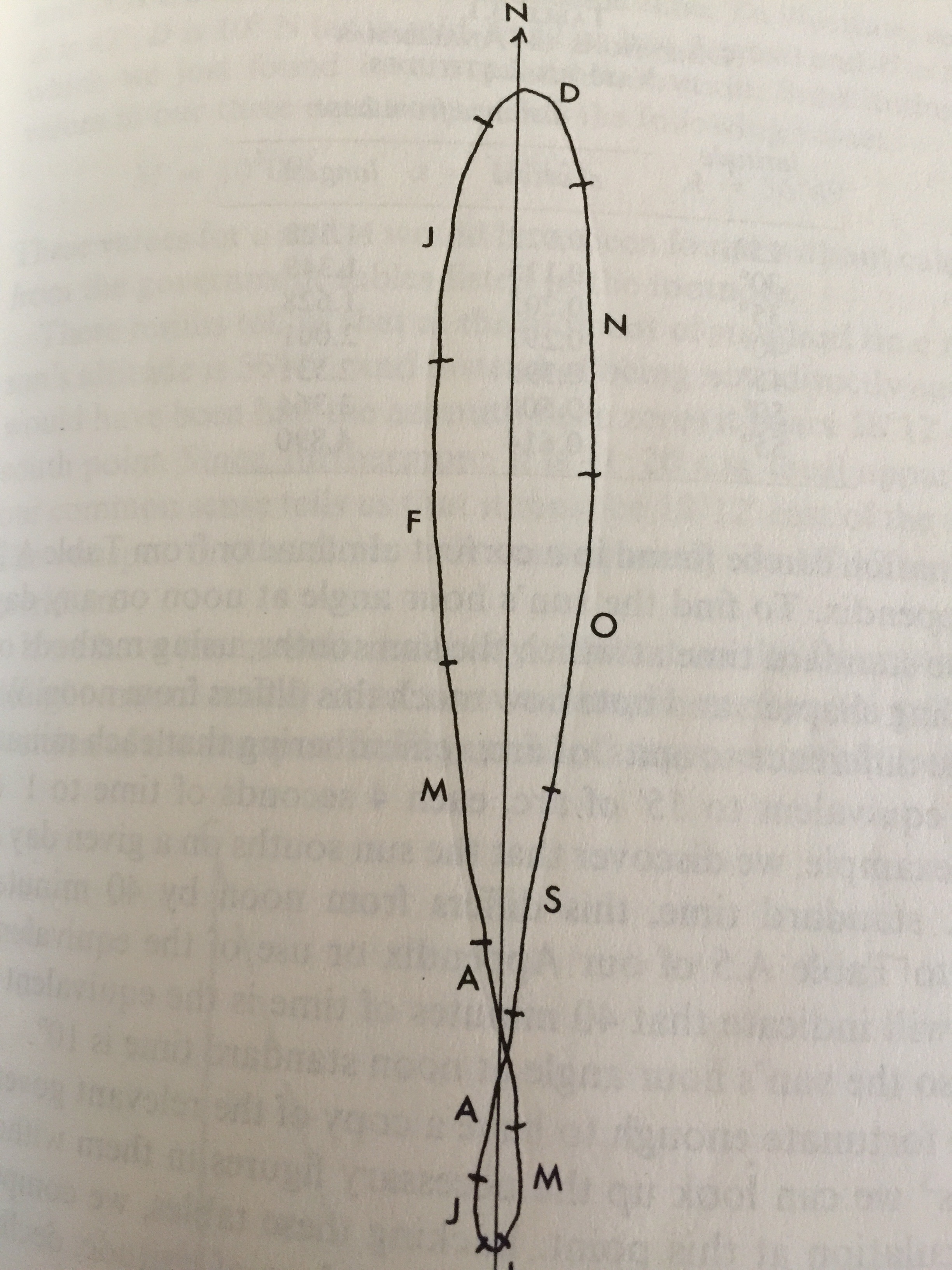

Analemma: The shadow caster is at the bottom, where the shortest shadow will be (summer in the Northern Hemisphere.) The areas to the right are where the Sun “runs fast” relative to clock time, especially in autumn, which gives rise to the very early sunsets we notice. In January and February, the Sun “runs slow,” and we see that as late sunrises but relatively late sunsets, too. We notice by Christmas that the Sun is setting later. The vertical line is neutral. Four times a year, Sun and clock time are the same.

Analemma: The shadow caster is at the bottom, where the shortest shadow will be (summer in the Northern Hemisphere.) The areas to the right are where the Sun “runs fast” relative to clock time, especially in autumn, which gives rise to the very early sunsets we notice. In January and February, the Sun “runs slow,” and we see that as late sunrises but relatively late sunsets, too. We notice by Christmas that the Sun is setting later. The vertical line is neutral. Four times a year, Sun and clock time are the same.