It’s not every day I get interviewed for Nebraska Life magazine. Or give the interviewer goosebumps. Like everything else that had happened in the prior two days, it was a matter of chance.

It was chance that as a Rowe Sanctuary volunteer doing daily cleaning, I decided to take a sweeper over to the viewing blinds, which get sand and small gravel tracked in. It was chance that led me to stop for a few minutes, delaying my return, because I saw a flicker come out of a cavity nest in a dead cottonwood. When one is volunteering at a bird sanctuary, things like a flicker’s leaving a nest are important matters.

The delay held me long enough on the trail that I encountered Alan, a little younger than I. He saw my name tag, recognized me, and introduced himself. I was a little embarrassed I hadn’t recognized him. I’m the same way with birds—good auditory memory, terrible visual. We knew each other from past years, since he also volunteers at Rowe; judging by his shirt, he worked for Nebraska Life magazine as an assistant editor. I told Alan that I was once an assistant guide with him, and I emulated many of his traits. Alan smiled, then asked if he could interview me for a story. Why not?

We talked about why I came to Rowe and what the cranes meant to me. He then suggested that we go into Jamalee Blind to shoot some pictures of me, while I swept the carpet. Why not? And I told him about the story that happened two nights prior, in East Blind.

I didn’t go into all the details, such as my 11 hour trip from Eugene to Kearney, leaving me frazzled when I arrived. I probably should have gone to bed early and not bothered the public with my mood. Instead, I went to the viewing blind that evening with Jane, an experienced volunteer ten years my senior. It is always good to see Jane each year and even better to go out into the blind with her. She’s a solid Nebraskan who knows what’s she’s doing, telling me that while she wanted to talk to the thirty-two visitors first, she thought I should say more, because she learned from me every time I spoke. I could say the same thing about her.

At that time of day, I wasn’t sure I was capable of meeting her expectations, but said nothing. We had a good group who asked great questions, and the cranes put on a nice show, flying over several times, as they do in early evening, before they landed on the river. It was still early, and I quietly strolled back and forth in the blind, making sure people were properly situated. And then came the the story I related to Alan:

As I reached one end of the blind, a woman asked me, “You said that seeing the cranes were one of your top three sights in nature. What were the other two?”

I stopped and looked at her: “A total solar eclipse and seeing a wolf in the wild on Isle Royale.”

From behind, I heard, “Did you know there are only two wolves left on Isle Royale?” I turned around, seeing a tall man with a kind, somewhat concerned face.

“Yes,” I replied. “I don’t know what is going to happen next.”

“I’m involved in some of that for an environmental group in Minnesota.”

That was interesting. I told him I was a member of the Friends of the Boundary Waters, a small organization in Minneapolis that leverages a few paid staff members and several thousand members to accomplish good things.

“I was their first liaison to the northern communities.” That stopped me cold.

“We know each other,” I said, with a little more excitement. “What’s your name?”

“Ian.”

“Mike Smith.”

Ian paused, his eyes briefly questioning, then I saw the sudden change of recognition in his face as he realized who I was and that we indeed had met each other in person in northern Minnesota four years earlier at an annual scholarship banquet for Vermilion Community College. In 2008, I established a scholarship at Vermilion, splitting the funding with the Friends. Four years later, the Friends established a liaison for the northern Minnesota communities, Ely especially, and Ian was the person “on the ground.” We jointly presented the scholarship for two years. We shook each other’s hands, talked for a few minutes, and then it was time for him to look for cranes and for me to walk back down the blind. As I left, he shook his head in disbelief. I suspect I did the same thing.

Viewing wildlife is a matter of being in the right place at the right time, having all senses open, and being ready for the unexpected. It’s all about recognizing opportunities when they occur.

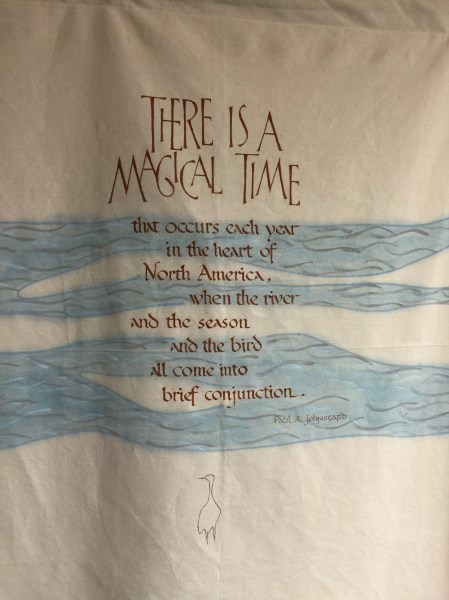

I hadn’t ever imagined I would encounter somebody in a viewing blind whom I knew from somewhere else. Paul Johnsgard, one of the leading writers about cranes, speaks of the conjunction of spring, a river, and a special bird. Ian and I had supported a special wilderness 1000 miles away. By chance, we arrived in the same viewing blind at the same time in another special place. Several unlikely utterances had to occur for each of us to discover the other’s presence.

Underneath my jacket, not visible, was my shirt, which was “Isle Royale National Park.” I had never worn that shirt before. Of all the shirts I could have worn, I chose that one.

I had had a long, unpleasant day. But again, being among the Sandhill Cranes was magic. My telling the story gave Alan goosebumps. I saw them myself.

There was more than one conjunction that night on the Platte.